There is a growing body of research that focuses on “smart aging.” We often think about our body’s memory being limited to our minds, but the results of our activity and inactivity are stored in our muscles, joints and other systems of our bodies.

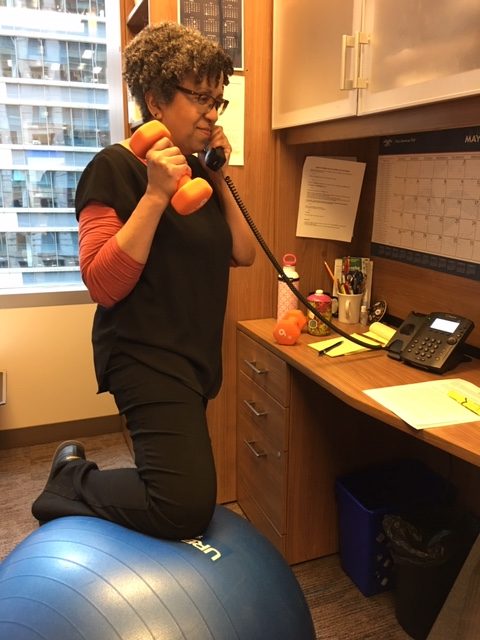

The youngest baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) are now in their 50s and 60s and redefining what it means to be “older.” Recent advances in the science of fitness provide an opportunity to improve quality of life and athletic pursuits well beyond what was typically accomplished by our parents. But at the same time, modern advances allow us to spend more time in sedentary jobs and activities, resulting in a crossroad which could lead to worse fitness than our parents.

Related: Invaluable Benefits of Exercise for Aging Populations

I myself am a boomer as well as a personal trainer, lawyer, wife and mother. I can fully appreciate how a busy life can contribute to underutilization of muscles needed for activities of daily living (ADL).

Below are three fitness activities that can provide a challenge and allow you to assess areas where you might benefit from strength and flexibility training to improve your ADL at any age:

Walk around with a 30 lb weight for 1 minute and work up to 10 minutes

Pick up a 30lb weight and walk around. Move it around in different directions and heights. It is the weight of the average 2-3 year old child. Even if you have no intention of carting around a kid, it is a great measure of what muscles might be compensating for other weaknesses. If you don’t belong to a gym, you can do the same thing in a store holding a comparable bag of dog food or garden soil. Was there a position or height that was more difficult?

At commercial time when watching TV, get down on the floor in a cross–legged position and then stand up 10 times – 5 times each side

I didn’t say this would be fun, but it can be very effective to determine which side is easier to get up from and what muscles you used to do so. Experiment with rolling to the side so you are pushing up with one or two arms as well as whether you can get up from a lunge position without using your arms. Was one side or position easier than the others?

Related: Think you may have a muscular imbalance? Here’s how Pilates can help

Walk up and down the stairs in super-slow motion

Falls are a leading cause of injury and virtually all of us have missed a step and taken a tumble that could have been mitigated if all of the muscles in the kinetic chain were working at optimal capacity. Walking up and down the stairs in slow motion allows you to assess where there might be instability at some point in the kinetic chain: It could be foot, ankle, knee, calf, hamstring, quads, hips or even abs that are tight or weak. It is a great opportunity to assess what muscles need more flexibility or strength (or both). Did you lean more to one side than the other when going slowly? Was it harder to maintain balance when ascending or descending? Did you use the railing and at what point?

Post written by FFC Contributor Linda Goldberg.

For questions or to share your learning, Linda can be reached at lgoldberg@ffc.com.